Bill Viola Michel-ange

THE ESSENTIAL DIALOGUE

Immerse yourself in the latest exhibition at London’s venerable Academy of Arts until 31 March. An unprecedented dialogue spanning 500 years between the brilliant American video artist Bill Viola (68) and Michelangelo confronts visitors with nothing less than humanity’s greatest metaphysical questions – life, death, rebirth.

By Xavier Flament in london - 02/02/19

Design: Benjamin Verboogen

1 BIRTH, LIFE, DEATH

The exhibition opens powerfully with the first of three juxtapositions spread through twelve rooms of the museum. In his famous “Nantes Triptych” (1992), Bill Viola presents 30 minutes of a woman giving birth and the dying moments of his own mother – two compelling instants (all there really are, perhaps?) separated by a ghostly allegory of life passing.

AND OPPOSITE...

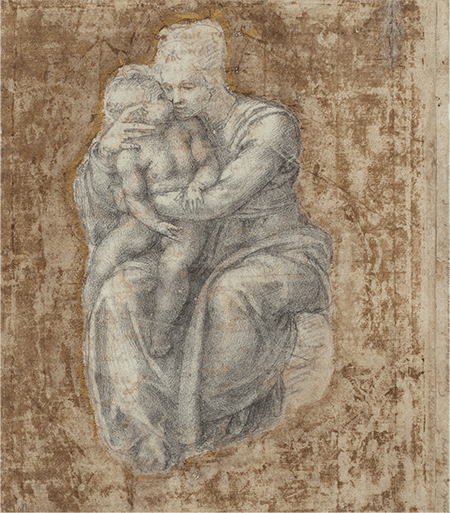

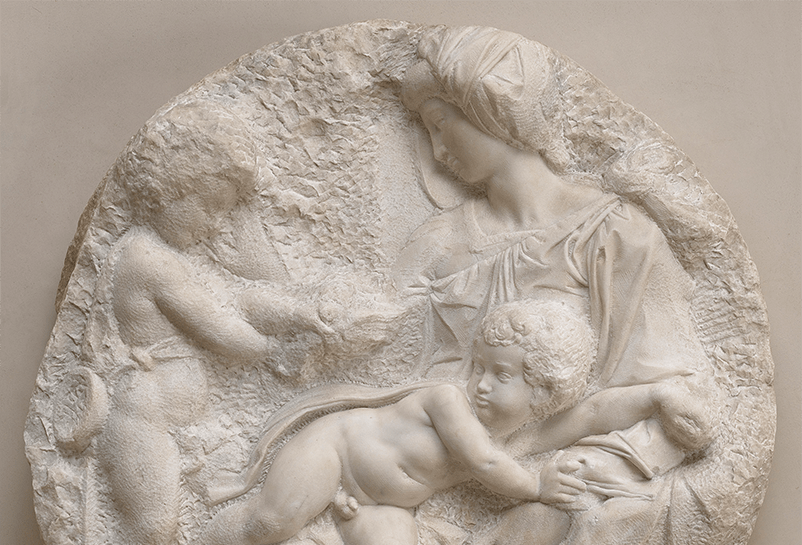

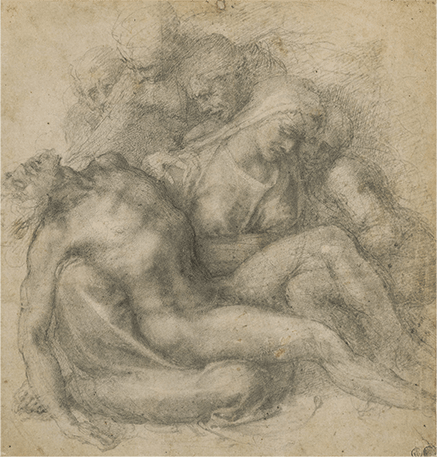

Opposite each element of the video triptych there is a work by Michelangelo: birth with two Madonna and Child images, and death with a Pietà, belonging – like most of the other drawings in the exhibition – to the Queen’s Print Room at Windsor Castle.

Meanwhile, the Royal Academy’s celebrated “Taddei Tondo”, an unfinished marble relief, symbolizes the passage of life through the presence of John the Baptist, who announces Christ’s destiny.

INTIMATE

Rather than the awe that Bill Viola’s work usually evokes, this confrontation allows space for a much more intimate feeling.

Visitors are addressed directly, enabling them to project their own emotions and experiences and to take ownership of the great questions that the two artists explore in parallel. The result is a three-way exchange on these most fundamental of themes.

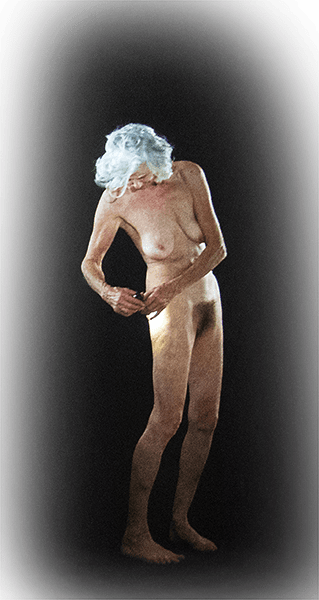

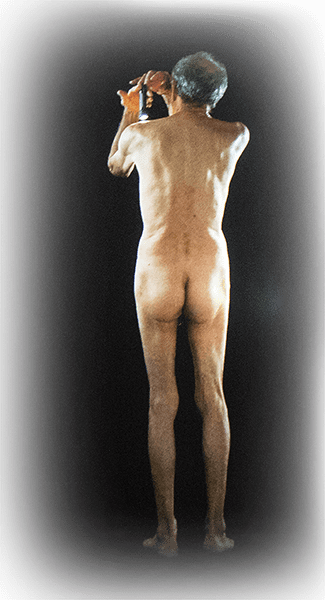

2HUMAN BEINGS AND ETERNITY

Bill Viola, Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity, 2013

© David Parry / Royal Academy of Arts

WHERE IS THE LIGHT?

Bill Viola spends his time interrogating time’s passing. His art is itself a reflection on the span of time. This is what he represents in this ageing Adam and Eve, naked as the day and exploring each part of their body, flashlight in hand. The man hopes to discover immortality; the woman eternity. The tiny light is obviously the lens of an artist who has been searching for immortality and eternity for almost 40 years.

“ It is the image of that inner state and as such must be considered completely accurate and realistic. ”

Bill Viola, 1981

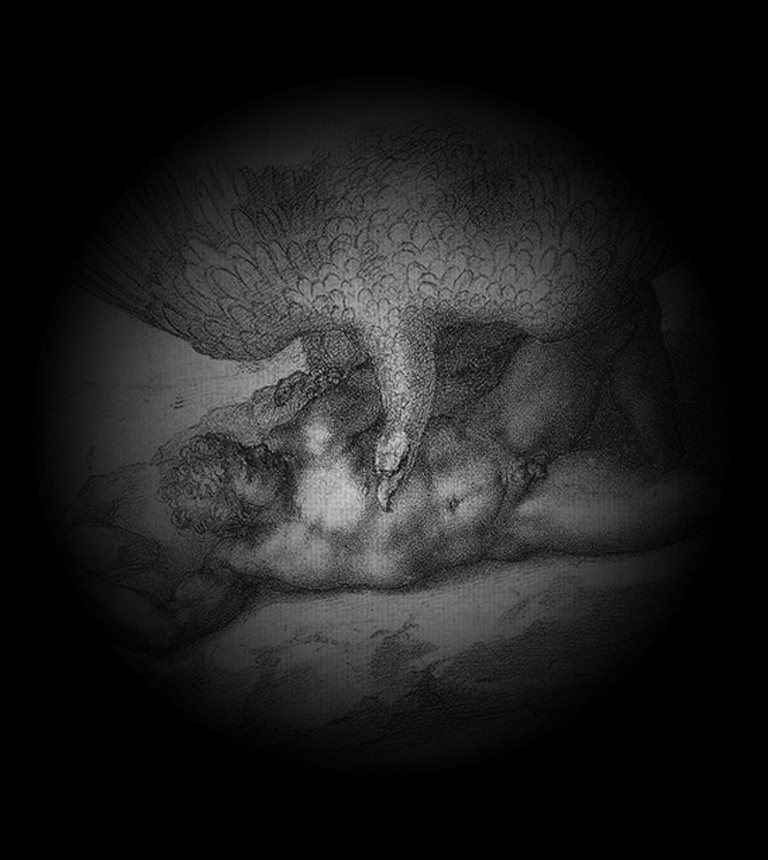

DIVINE PUNISHMENT

With our magical faith in technology, we’ve lost sight of the divine punishment to which our pursuit of immortality lays us bare. Which is what Michelangelo reminds us of in this second juxtaposition. Particularly in this “Punishment of Tityus”, made in 1532 – a period in which the artist produced one resurrection after another. The theme recalls that of Prometheus, chained to a rock for stealing knowledge from the gods and giving it to humans. The giant Tityus attempted to rape Leto, his father’s mistress. Not the wisest move, given that his father was Zeus. He ended up having his liver devoured for all eternity.

“My soul, which speaks with death, and with it takes stock of its own situation, and is continually weighed down by new anxieties, hopes day after day to leave the body.”

Michel-Ange, c. 1524

«Tityos», Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1532.

© Prêt de Sa Majesté La Reine Elizabeth II

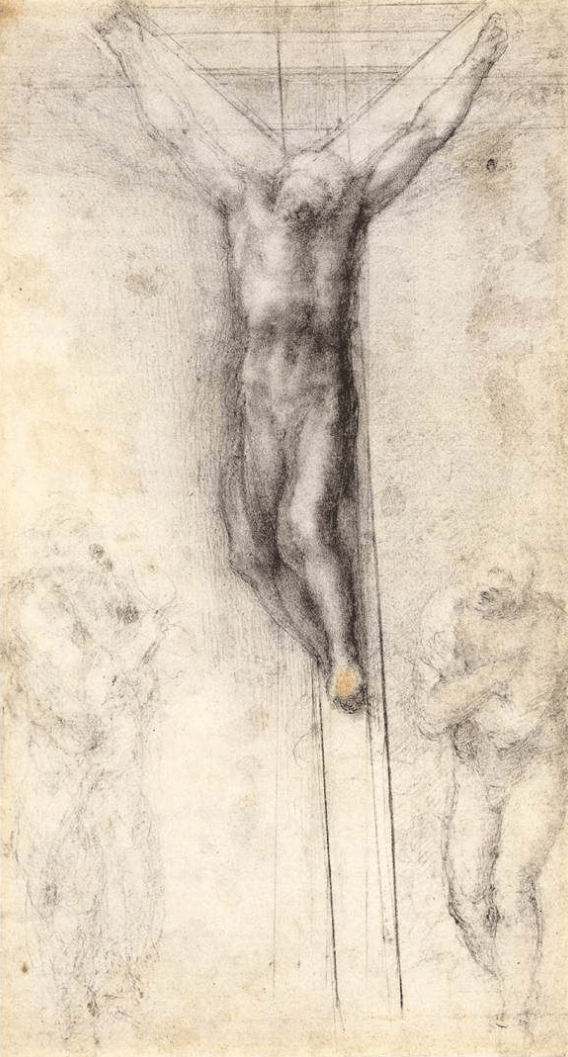

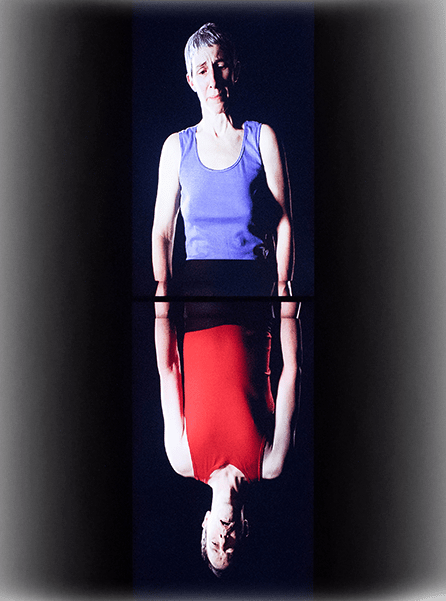

3 RESURRECTION OR REINCARNATION?

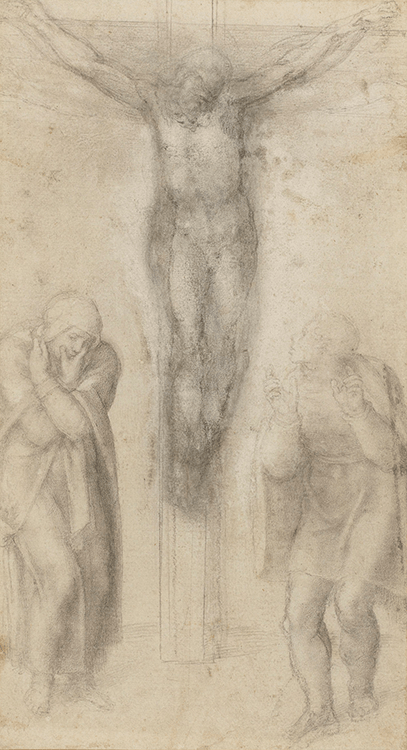

The third and final dialogue asks what becomes of us after we make our grand exit. Two Michelangelo Crucifixions surround Bill Viola’s “Surrender” (2001) – a pair of reflected figures, overwhelmed by the Passion. They grieve in slow motion before their bodies dissolve into pure, eternal colour.

SALVATION FOR ALL?

Michelangelo created a dozen Crucifixions in the 1560s – each one a meditation on Christ’s sacrifice, in which the artist represented the soul’s liberation from its fleshly husk as he himself grew steadily closer to death.

“Neither painting nor sculpting can any longer quieten my soul, tuned now to that divine love which on the Cross, to embrace us, opened wide its arms.”

Michel-Ange, c. 1552-4

WEST OR EAST?

Here once more, the question is what happens after we depart this life? The historical figure offers the Christian response, while his modern counterpart is more ambiguous. He hesitates between resurrection in the sublime “Tristan”, which closes the exhibition, and the eternal return of his “Messenger”, which opens it.

It’s a bold exhibition for an institution that’s 100% private yet fiercely defends its identity as an academy of arts: educating the public through a curated artistic heritage, while laying the ground for the visionary creations of the future.

“It is not the monitor, or the camera, or the tape, that is the basic material of video, but time itself.”

Bill Viola, 1989